Words: Chris Moran

By rights, skateboarding and snowboarding should be intertwined; they are family after all. But whereas we used to high five, in recent years our skater cousins have left us hanging. It's the classic icy-shoulder at a family wedding moment. My own brother Pete summed it up once when I met him wearing a pair of Volcom jeans and a Saville-Row suit jacket I’d just found at Oxfam. I thought the look I'd assembled was half debonair, half derelicte. Which is to say, cool. I met him in my customary way. “Waaaaassssuuuuup.” I said, bending at the knee.

“You look like Jeremy Clarkson,” he said, with his skateboard at the end of his tattooed arm. “You wanker.”

So where did it all go wrong? I'm certainly old enough to remember when snowboarding was being touted as the coolest sport in existence. I've got a copy of The Face magazine from back in 1996, with Nicole Angelrath as its star attraction; I've got the famous edition of Rolling Stone Magazine with Shaun White on the cover, under the headline ‘Is this America's Coolest Teenager?’; and I was once interviewed by Russell-fricken-Grant whilst in a jacuzzi at the Daily Mail Ski show (yeah, before it was the Daily Mail Ski and Snowboard show). I fucking know what being cool is all about OK? I guess the question I’m asking then is: at what point did we snowboarders start getting dissed by our skateboard-riding bretheren? When did we – you know – lose our mojo?

The fact is, skating and snowboarding are both the illegitimate spawn of surfing, conceived in a very liberal-minded manner indeed. Skateboarding had a difficult birth: in 1961, Larry Stevenson was an enthusiastic surfer working on a publication named The Surf Guide, writing at a time when the sport’s popularity had started going through the roof. He came to the conclusion that the public's appetite for riding boards was at an all-time high. with The Surf Guide, he had the perfect opportunity to promote a cross-over activity, and ploughed money and time into what he knew as ‘sidewalk surfing’ (or ‘skateboarding’ as others had started to call it). Homemade boards had been popping up since at least the late 1950s but the sport had never had its own manufacturer. In 1963, Stevenson’s Makaha Skateboards opened for business in Santa Monica, California. Emulating surfing’s commercial model, and even naming the company after surfing’s most famous contest (the Makaha Surf Festival) he formed a sponsored team just like the surf brands, put on contests to promote the sport (using surf competition rules) and gave exhibitions in places where he knew surfers would be watching – the most likely candidates to take up the sport.

According to Concrete Wave, the History of Skateboarding, Stevenson's efforts paid off. Between 1963 and 1965, roughly $4 million worth of skateboard equipment went through Makaha's books. Unwittingly, however, he also became the first skateboard manufacturer to encounter a fundamental problem with the sport. While surfers only really interacted with other coastal users (mostly swimmers and the odd fucked-off fisherman) and largely confined their activities to the beach, an increasing number of skateboarders found themselves confronted with pedestrians and traffic. Made up primarily of teenagers, the young sport was in no position to form an adequate stance against the mounting resistance from police chiefs, city councilors and letter-writing busybodies, who naturally condemned these youngsters as an unwanted nuisance. By the summer of 1965, 20 cities across the US had banned skateboarding. The sport had nowhere to go and sales dropped accordingly. In an interview for The Skateboarder's Bible, Stevenson said: “I can just about recall the week, if not the day. It was mid November 1965 when things just died. One week I was getting so many orders people were leaving them on my doorstep so I'd see them when I left for work in the morning. The next, I was getting 75,000 in cancellations in a single day.” By 1966, Makaha declared bankruptcy, and the sport had completed its first boom and bust cycle.

Not that snowboarding had an easier upbringing. While Stevenson and co were grappling with the urban authorities, ‘snurfing’ – as it was known in the 60s – was also widely dismissed as a passing kids’ fad. Nevertheless the seeds of the sport had been sewn, and in early 1971 Surfer Magazine ran an interview with an ex-world champion who detailed a dream he’d had about riding down snow-covered mountains. A reader and surfboard-shaper on the east coast of America named Wayne Stoveken wrote in to the letters page explaining that he was already working on such equipment, which led another reader – a Dutch-born design student by the name of Dimitrije Milovich – to seek out Stoveken. When the two men met, they naturally took Stoveken's boards for a test run in the snow and Milovich was hooked. “That was the coolest thing I ever did,” he explained in a recent interview. Milovich invited Stoveken back to his digs at the University of Utah so they could experiment with their new boards and test them some more in the famous local powder. Milovich hitch-hiked to the newly-opened resort of Snowbird in late 1972 to show the resort owner and big wave surf legend Ted Johnson the ideas he and Stoveken had been working on. Johnson liked the look of this new ‘snowstick’ or ‘winterstick’ (as Milovich was calling the designs) and agreed to let the pair use the resort for testing.

Such pro-active moves would prove essential for the sport’s future success, but in this instance it didn’t lead to a great deal. Stoveken eventually returned east, while Milovich stayed in Utah, continuing his studies and perfecting his powder riding, until he eventually scored an article in the March 1975 edition of Newsweek Magazine – snowboarding's first major publicity breakthrough.

Now that photos of snowboarding were starting to appear in big publications, other innovators followed, setting up their own companies and tinkering with the design of their boards. By 1977 the scene was set for Jake Carpenter of Burton Snowboards and Tom Sims to start their great rivalry, and for the next few years teams led by either Sims or Carpenter won every competition there was, giving snowboarding’s evolution a head of steam. Soon riders had better, purpose-built bindings, metal edges, fins and, by 1980, p-tex bases – the same cutting edge technology used in skis. While all this sounds like a smooth ride, the bottom line was that there were still few resorts that would allow riders to use their lifts. As the early 80s progressed, only a handful of ski areas in the US had given snowboarders the green light to ride there. If the sport was going to succeed, someone was going to have to spend a good chunk of time lobbying resorts to open their doors. Milovich didn’t want anything to do with it and dropped out of snowboard manufacturing for good; Sims opened up a few resorts around Tahoe; Jake Burton Carpenter, meanwhile, cold-called resort owners across the US. It would take a solid decade to start taking effect.

So, neither snowboarding nor skateboarding were welcomed into the world with open arms. Throughout the 1970s and 80s, in fact, they were both being brow-beaten by people who didn’t want them to succeed. In skating – almost driven out of existence at one point – what they first needed to do was to re-establish themselves. In 1970 Frank Nasworthy chanced upon some urethane rollerskate wheels and realised they were far superior to the crumbly, hard, clay wheels he and his peers had been using. He set up ‘Cadillac Wheels’ in 1972, took out ads in all the surfing and skateboarding mags and pumped enough money into the promotion of the new urethane product that another boom in the sport followed. Was Frank a cool guy? Well, he liked to be referred to as ‘Captain Cadillac’ so the jury is still out on that one. What is certain is that his new wheels gave skaters everywhere the ability to trust their board. Before that, clay wheels added a fantastically dangerous ‘wild card’ element to pavement riding, and with a better product, skaters of the day advanced in huge leaps and bounds – both figuratively and literally. In 1975, Alan Gelfand worked out how to ollie – jumping the board off the ground using only one’s feet – which broke the sport free from its surfing roots and enabled skaters to explore city streets through new eyes. “Two hundred years of American technology has unwittingly created a massive cement playground of unlimited potential,” wrote Craig Stecyk in The Skateboarder in that same year, “but it was the minds of 11-year-olds that could see that potential.”

Hot on Gelfend's tail, the Zephyr team of Dog Town and Z-Boys fame pushed their skateboards to the limits, inventing a whole new subculture and venue for skating when, during the summer drought of 1976, they cleaned out empty swimming pools and skated them. It had been done before – The Quarterly Skateboarder had published shots of people skating pools as far back as 1965 – but the Dog Town crew added illegality, attitude and style to their pool antics. When punk music hit the states the following summer, skateboarding was perfectly placed to embrace the movement and stand side by side as a symbol of the counter-culture movement sweeping the world.

But while that was true for certain underground factions within skateboarding, it’s also true that most skaters at this point were headband-wearing geeks who endlessly practiced their rear wheel spins or twirlers and weren’t above wearing matching team shorts to enter the various competitions springing up around the US. In 1977, for example, halfpipe riding was invented by a curiously un-cool Canadian stuntman and promoter named Wee Willie Winkles (his trademark was three ‘W's floating across his skateboard), who built a flat-packed, tow-able ramp he could use for demonstrations. “I saw [Zephyr team members] Jay Adams and Tony Alva skating back and forth between two quarterpipes,” said Winkells in a recent interview, “and it occurred to me that these two could be joined together to make a much smoother transition.” Pictures of Winkles show a shifty-looking guy in McEnroe-tight shorts dropping into a very shonky mini ramp indeed. People were naturally skeptical. In the UK, one magazine noted that skateboarding sales were up and suggested such an industry might only make money should “… skateboarding out-last the duration of the hula-hoop craze.”

Such fears were justified during the 1980s, when skateboarding went through yet another boom and bust period. Its rise was assured with the 1985 release of Back to the Future, turning hundreds of thousands of young minds around the world onto the possibilities of riding a board with wheels (and most importantly, of holding onto the back of a car in order to get a free ride to school like the film’s star Michael J Fox). But the boom wasn’t to last and once again, liability lawsuits and increasing insurance premiums shut most skateparks, while councils and police departments got increasingly enraged over skaters grinding stairs, handrails and other pieces of architecture. Arrests and decline followed. Skaters produced stickers reading ‘Skateboarding is Not a Crime’, though clearly, in some parts of the world, that’s exactly what it was. The industry responded by going underground, and began to demonize non-skateboard companies who had tried to join in the party – those seen as only in it for the money. The thinking was that their heavy product marketing eventually led to hype, over-inflation of projected sales, and an inevitable surplus of stock which had bankrupted core skate shops. Skaters themselves started their own brands, filmed their own videos and retreated into an insular, hardcore society that retained a strong ‘fuck you’ image – best embodied, perhaps, by the fantastic Big Brother Magazine, first published in 1992. Articles such as ‘How To Make Your Own Acid’ (published in the so-called ‘Kids Special’ issue), cover photography featuring painted dwarfs and editorial content that often verged on the pornographic eventually drew the attention of America’s mainstream media, who cooked up a storm of rightful anger. But while parents and church groups stood by thoroughly shocked, skaters themselves took it all with the heavy dose of irony that was clearly intended. Things were muddied, however, when the famous pornographer Larry Flint bought the title, only to run it into the ground before the end of the decade. The slump was blamed on poor sales and production budgets, but it can’t have helped that the Big Brother editorial team started attacking the disabled community, of which Flint is wheelchair-bound member.

There’s pushing it, and then there’s really pushing it.

It’s at this point – as skateboarders were fine-tuning their middle finger attitude – that snowboarding also started to enter its rebellious teenage years. Big Brother produced a sister snowboarding mag named Blunt (a nod to the weed smoking young snowboard community) and skaters started to look at this growing winter activity as a cool thing to do. As far back as the late 80s, skate pioneer and Bones Brigade member Steve Caballero had learned to snowboard, and was an instrumental participant in the first freestyle competitions. Caballero, famous for inventing the ‘cab’ – a backwards to backwards 360 spin – rode in the Lake Tahoe region of Northern California with snowboarding pioneers such as Terry Kidwell. He helped give rise to the first ‘pro model’ snowboards, grabbed a spade to help dig the first halfpipes, and generally steered the sport towards the pro skater model it still follows today. By the early 90s, the crossover between sports was huge. Santa Cruz skateboards started to make their first snowboards in 1990, opening the gates for fellow skate companies H-Street, Plan B, World Industries and many others. Pro skaters followed suit. American skateboarder John Cardiel emerged as the decade’s best cross-over pro, blurring the lines between tricks on concrete or snow, while fellow skaters Noah Salasnek and Danny Way both signed to brands that made snowboards and skateboards (Sims and H-Street respectively). Noah’s pro model snowboard was even made to look like a battered old skateboard, with a base graphic featuring trucks, wheels and boardslide scratches.

Prior to the mid 90s, snowboarding’s style and trick list was also shamelessly taken from skateboarding. Competitors rode halfpipes and funboxes – both obstacles from skate parks – and threw grabs that had been perfected long ago by their four-wheeled-cousins: frontside airs, indy grabs, methods, ollies, riding switch, going fakie, rock and rolls, smith grinds and lien airs to name just a few. It wasn’t just the actual tricks, either, it was the spirit behind them. Just as in skateboarding, making things look good was paramount, and if you could do so effortlessly you were king. Aesthetics ruled.

By 1994, however, the channel of influence had started to flow back the other way, and snowboarding actually influenced skaters. For a while, skating had been heading down a freestyle cul-de-sac that was all about small wheels and super tech flip tricks. Now ‘going big’ – a staple of the growing snowboard repertoire – made it back into skateboarding and was combined with new school steez. “If skating hadn’t disappeared up its own arse for those years,” says Ben Powell, editor of Sidewalk Skateboard Magazine, “I think we’d still be doing ollie grabs off street ramps.” Instead, jumping over wide, injury-defying gaps were all the rage in both sports, late spins ruled and styled airs were in. Magazines such as Freestyler in France began to print predominantly snowboarding features in the winter and skateboarding articles in the summer. By the mid 90s snowboarding’s popularity was multiplying like a virus. And having emerged from its poorly advised neon period, it was also attaining some sort of credibility within the board riding community. In an article entitled ‘When Did Snowboarding Get Cool?’ the American writer Chris Stepanek distilled the movement down to one line: “In 1994, every kid and his brother sold their skis, bought a pair of big pants, the latest Nirvana album and a snowboard.” While there were hiccups along the way, moreover, snowboarding never hit the boom and bust cycle, and its trajectory has been – so far – a fairly even upward curve.

So why couldn’t this brotherhood have lasted? The crucial difference between the two, of course, was acceptability. “You were still paying for lift tickets so you were allowed to do what you wanted,” argues Ben Powell. “What we do is – and will always be – deemed illegal.” And with some semblance of respectability, snowboarding slowly started to drift away from its cousin sport. “The moment that skateboarders started to dislike snowboarding was at the end of the boozy clown era,” continues Ben. “I mean, those Scandinavian super athletes and people who actually train. Is that what it should be about?” John Cardiel had a similar take on it. In a recent TV show he explained why he turned his back on a burgeoning snowboarding career and instead sweated it out with the skate rats. “I was a pro snowboarder for like, four years” he said. “Skateboarding was better. You think about it, you've got to buy the boots, buy the snowboard, buy the clothes, buy the lift ticket; that's two hundred bucks just to fucking get up to the snow. You've got to be semi wealthy to even kick start the sport. [Then I was] around all these dudes who are professional at it, who grew up in Aspen. Whatever. Snowboarders. They don't fucking know hard times. We don't really vibe.”

Those words might strike a chord with some, but such animosity was pretty much one way. Snowboarders were happy to keep skating through it all, either oblivious to the ill-feeling growing in the skate community, or just able to deflect it. Heikki Sorsa, Marc Frank Montoya and Jussi Oksanen are just a few examples of talented riders who could probably have made a career out of either sport, and on every snowboard trip I’ve ever been on, there’ll always be someone who’s pretty good on a skateboard. And then of course there are the two enigmas in the equation: Tony Hawk and Shaun White. Tony because, in the most hardcore board sport there ever was, he’s the straightest laced, most run-of-the-mill superhero one could possibly imagine. The top of the coolest pyramid ever constructed and he’s one of the geekiest and gawky men ever to have stood on a board. Funny eh? And then there’s his vert riding protégé Shaun White, a kid who bypassed the entire skate industry and focused on snowboarding – winning Olympic gold and more X-Games medals than he can probably remember – yet whose undoubted talent on a four wheels is largely un-noticed by the skate fraternity. “He’s a hard one to pin down,” says Ben Powell. “He doesn’t get coverage in the skateboard media like Thrasher or Slap, because he’s seen to have sidestepped the old fashioned way of getting recognition. He’s not hated, no way, but he doesn’t fall into the category of someone who’s paid their dues. He just has no currency in the skateboard media.”

So is it all lost? Will we ever merge back as one, holding hands under a huge rainbow to slide off sideways into the sunset? “Don’t get me wrong,” says Ben, “these days there’s definitely less of that ‘selling out is bad’ bullshit in skating. I mean look at that anti-Nike sentiment there used to be, whereas now people have seen what they’ve done for skating and they’re like, ‘OK that’s a good thing.’ And I think economically we’re getting closer. You’ve only got to look at Burton snowboards buying Alien Workshop to see that.” Ben talks about the potential reasons skaters moved away from the snowboard scene. “Hatred is probably too strong a word for it,” he says. “But the way a lot of skaters saw snowboarding just explode in popularity, and the big name riders were earning ten fold what the skaters were, and a lot of that was using ideas ‘nicked’ – to use the parlance of the day – from us.” So is that all water under the bridge? Is a reconciliation on the cards? “It’s funny ‘cos we’re all getting older aren’t we?” he continues. “And there’s definitely a huge older skate scene out there now. If you’re 35 or 40 years old and you want to start skating again, what are you going to do? Go to the local car park and grind some curbs while the kids in New Era caps take the piss? No one’s going to do that. But with the whole explosion in skate parks happening, it’s a lot easier for dads to go skating with their kids, and it’s a lot harder for people to knock that, so yeah – skating is broadening out. And this hasn’t ever happened before, I mean when I was a 20-year old skater, the oldest skater I knew was 25. There’ll always be the core element to it, but there’s a whole strata of kids who’ve gotten into it via the X-Games and know nothing about the punk skate movement of the 80s, and likewise, there’s an older generation of guys who don’t care about video parts or progression but just want to ride a board in a concrete bowl. A lot of the cultural baggage has gone, so yeah, there’s probably skaters out there who’ll want to be friends with you lot.”

For the minute, I reckon that’s about as close as we’re gonna get to a reciprocated high five. And with my pinstripe jacket hanging squarely on the back of my chair as I type this, I’ll take that.

SIDEBARS…

Switch Stance: Snowboarders Who Skate

Shaun White

First showed off his skate skills as a precocious 11 year old in legendary snow flick The Haakonsen Faktor. Brought under the wing of fellow vert legend Tony Hawk and still the only man to claim X-games golds in both skate and snow.

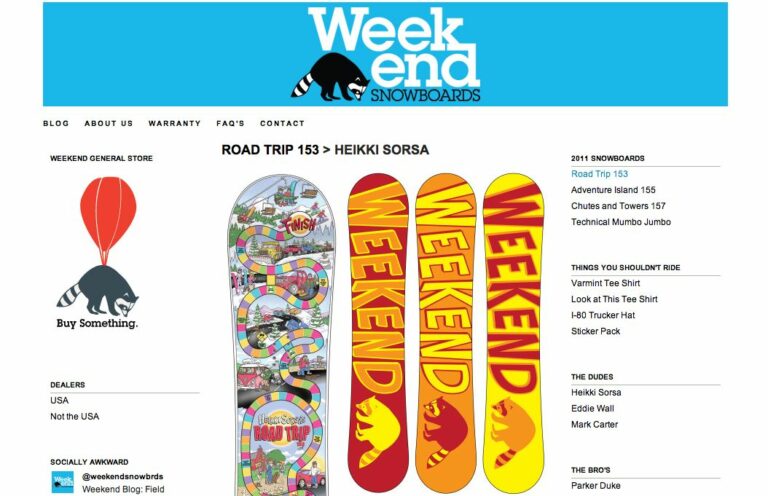

Heikki Sorsa

Pulls a sweet flip down a stair set in the Standard Film ‘Notice to Appear'. Was wearing a neon headband at the time, adding to skater resentment of us poncy snowboarders.

Eero Ettala

Switch double backflips at the X-Games and fuck off Helsinki rails are all good practice for a summer of ramp slaying.

Nico Droz

Has brought his French gangster style to snow and concrete for over a decade.

Pierre Rué

French rail protégé and star of the Homies films (given away on WL). Also a damned steezy street skater as witnessed by the photos in this article.

JP Walker

His incredible backyard skate ramp was shown off MTV-cribs style in the extras to the 2001 Forum movie ‘True Life'.

Jeremy Jones

Could snowboarding’s ultimate rail monkey do anything but skate in his free time? Thought not.

Jussi Oksanen

Famously rides a skateboard goofy and a snowboard regular. Apparently it’s because his first (second-hand) snowboard was set up regular.

Mikkel Bang

Was seriously good at skating and snowboarding at 13. You seen him ride a snowboard recently? Nuff said.

And a few from the UK…

Tyler Chorlton, Scott McMorris, Ben & Sparrow Knox

All more than capable of holding their own amongst the cool kids at a skatepark near you.

Skaters Who Snowboard(ed)

John Cardiel

Skate legend who became a snowboard pro for four years, before returning to his roots and bringing snowboard-esque air to concrete bowls. Interviewed later in this issue.

Noah Salasnek

His famous knock-kneed snowboard style was drawn directly from his background as a skate pro. Made the transition to snow and was instrumental in bringing freestyle to the backcountry of Tahoe and Alaska. Had a pro model graphic on Sims featuring skate trucks and wheels.

Steve Caballero

Inventor of the ‘caballerial’ or ‘cab’ 360. A bona fide legend of skateboarding, he also rode with shred pioneers like Terry Kidwell and helped ensure the developing sport was more heavily influenced by skating than skiing.

Tom Sims

West Coast skater and snowboard pioneer who had the vision to see halfpipes and big air – not hard boot racing – was the future. Sims’ skate business branched out from decks to snowboards and for a time rivalled Burton, only to run into financial difficulties.

Tony Hawk

The biggest name in skateboarding – and arguably action sports – has been known to hit the mountain. But can he hold his own against Shaun in the pipe? We suspect not.

Danny Way

Was a pro snowboarder for a short time and and rode for crossover brand H-Street. If there’s one skater who has applied snowboard thinking to skating it is this guy. Think massive transitions and burly, floated 360s. Think jumping the Great Wall of China. Think nutter.

Smash and Grab: Tricks we stole from skating

Indy – Or should that be frontside air? Cos, like, you know, you can only technically do a proper indy (sorry, frontside air) on a vert ramp, yeah? Why? Oh, go and ask some tedious skateboarding goon.

Lien – The universally loved Neil Blender bequeathed this trick to the world – essentially a boned-out melon on the frontside wall. Lien = Neil backwards, see? It became an instant classic, maybe because, like the method, it is a real barometer of style.

Method Air – Ever seen that Bud Fawcett picture of skate/snow crossover king Terry Kidwell doing a method air out of Tahoe City pipe circa 1985? Go and have a look, accept that fact that he did them better than you’ll ever do them (before you were born, probably), and that he did it all on a board most of us would struggle to carve.

Crail – Another vert skating classic, it’s something like a mute stiffy on the backside wall, and Jeff Brushie did them better than anyone, snowboarder or skateboarder. Fact.

McTwist – Conjured up one fateful night by Powell legend Mike McGill, the McTwist – an inverted 540 with a mute grab – quickly crossed sports to become a snowboarding must-do, and was recently updated by Shaun White with his ‘double’ version, just in time for the Olympics. To land one, you need a foam pit provided by Red Bull and your own private helicopter. No wonder they hate us.

Cab – Now a term applied to any switch frontside spin, the original ‘caballerial’ was named after skate legend Steve Caballero and consisted of a fakie-to-fakie 360.

Ollie (and Nollie) – Does jumping off the snow with a board actually attached to your feet constitute the same mindblowing leap as Alan Gelfand’s first skateboard ollie? Probably not. Do we care? No.

Stalefish – Tony Hawk coined this one when he perfected the grab on a Swedish skate camp. At dinner he described the miserable local food as ‘stale fish’ and a fellow camper thought he was referring to his new trick. It stuck.

Frontside/Backside Boardslide – The question everyone asks is: ‘Why is it called a frontside boardslide when the take-off looks like you’re spinning backside?’ The answer: In skating, frontside means the rail is in front of you as you approach it, backside means it’s behind you. Hence a ‘backside lipslide’ looks like a frontside boardslide once you’re on the rail, but is still ‘backside’ because you approach with the rail behind you. Confused? Good.

Tricks skating stole from us…

All the grabs – Controversial? Well maybe, but there’s a case to be made that with all that edge to play with, you can do ‘em better on a snowboard. Consider the Jamie Lynn method. What skater did them with more style? We rest our case.

900 – It might have been Tony Hawk’s special move in the original Playstation game, but snowbarders had been doing ‘em for yonks.

Stupidly big jumps – You’re telling me Danny Way (another ex-snowboarding pro from back in the day; I bet that’s been quietly retired from his CV) wasn’t influenced by the size of snowboarding jumps and transitions when he came up with seminal part in The DC Video?

Double McTwists, double rodeos, double corks and other future skate tricks – You read it here first folks.

Tricks that can’t make the jump…

Cliff jumps – Definitely off limits to our four-wheeled brethren – the day any skater cab 5s a cliff like DCP’s and makes it look good is the day we might as well all pack up and go home.

The one where the guy did a half backflip and caught his board upside down on a parallel rail – You know the one. It’s on YouTube (tinyurl/ugly-rail-trick). Possibly the most un-stylish trick in snowboarding history. Everything about it is ugly. Sure, it is imaginative – in a ‘wonder what would happen if I put my finger in this plug socket’ way.

Kickflips, heelflips, hardflips etc. – And no, flipping it by the heel cup, à la Justin Allison in that old Dope video, doesn’t count. The Noboarding crew have at least begun knocking on the door with their no bindings steez, but for the foreseeable future, flip tricks are off the snowboarding menu. That said, imagine a Noboard kickflip off a twenty foot cliff. Even skaters would have to be impressed with that.

No comply – Terje closed the book on snowboarding no-complies with his little mini section in Subjekt Haakonsen back in the day, but the classic Gonz-style no-comply remains tantalisingly out of snowboarding’s reach.

Syringe Air – Straightening your legs mid spin – arms by your sides like a penguin – just doesn’t work without bindings. OK it might be a piss-take trick but Terje made them look rad as hell.

Christ Air – A favourite of Christian Hosoi. We’ve yet to see a snowboarder take off his bindings 20 foot above the pipe lip, grab his board in one hand and adopt the crucifix position… but we’d love to see one try.

The Powder Turn – The reason we all snowboard. If skaters only knew how it felt, they’d never take the piss ever again.