Published in Whitelines Magazine Buyer’s Guide Issue, Winter 2010-2011

Buying a snowboard can seem like a scary business. Dipping a toe into any manufacturer’s catalogue or having even the briefest of chats with a snowboard shop monkey will reveal a whole world of techy jargon that even the keenest of shredders may struggle to understand. But worry not prospective purchasers! Whitelines has whittled away the worst of the marketing-speak, and sifted through the bullshit to uncover the fundamentals of what makes a snowboard tick.

Put simply, there are three things that affect how a snowboard feels – the materials used, the shape of the board and its profile. Here’s our handy guide to how each these helps define your ride:

MATERIALS

The materials used in building snowboard contribute to two main characteristics – the board’s flex and its weight. More flexible boards will pop, turn and butter more easily, but will be less stable at high speeds. They tend to be used by jibbers, people who ride a lot indoors and beginners. Stiffer boards are better for going fast and big. They tend to be preferred by big kicker and big mountain riders. Lighter boards are obviously easier to spin, pop and jib with, but lighter materials are often more expensive. Witness the Burton Method, pretty much the lightest board ever built, which will set you back a cool £1,300.

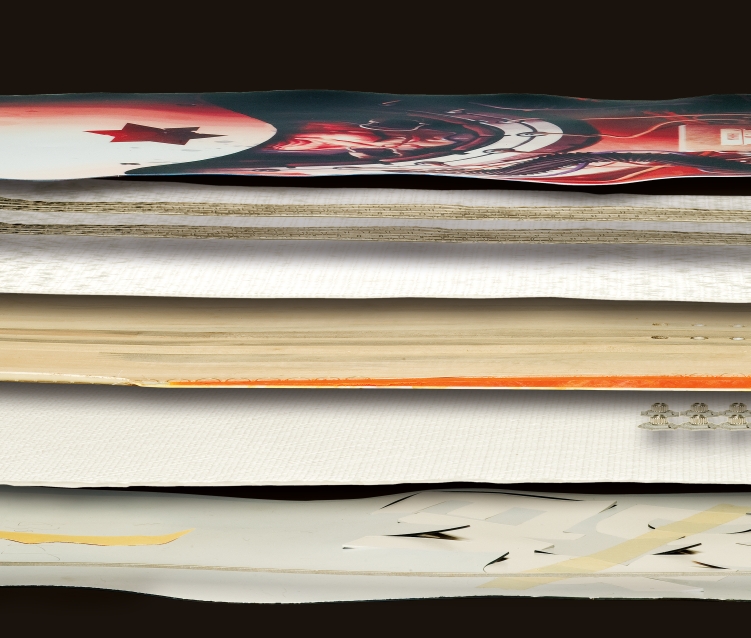

Topsheet – The topsheet is the bit of the board you see – you know, where that rad graphic goes. It’s normally made of plastic. Recently though, companies have started experimenting with different materials – Lib Tech use soya beans for some off theirs, while Ride use topsheets made of ethically-sourced hemp for some of their hippy free-ride models! While the materials used in the topsheet can affect weight and flex, in general they don’t change much more than how the board looks – which of course is one of the most important things right?

Strengthening Rods – Some boards feature rods of carbon or other materials on the outside of the core. These add stiffness, strength and extra pop. Structural Layers – Although companies like Lib Tech have started experimenting with more environmentally-friendly materials, the layers that surround the core of a snowboard are still normally made of fibre-glass. This is usually arranged in a grid along either two (bi-axial), three (tri-axial) or four (quad-axial) intersecting axes. These add strength and pop to the board. In general, the more fibre-glass axes there are, the stronger the board. Some manufacturers add extra dampening layers as well to reduce vibrations.

Core – The core is the heart of any snowboard. Running right down the middle of the board, it is usually made of strips of wood glued together. Different types of wood give boards different flexes and weights, but often a variety of wood-types are used in the same board, giving it different characteristics along its length. The most popular woods are poplar and aspen. Some more expensive cores are completely synthetic, for example Palmer’s Nomex honeycomb cores (made out of the same stuff as US fighter pilots’ suits!).

Sidewalls & EDGES – The sidewalls keep the guts of the board from spilling out. They can also help dampen the vibrations caused by shredding at speed. Companies like Ride have started making them out of urethane (the material used in skateboard wheels) to increase the dampening effect. The edges are made out of stainless steel and usually run all the way around the board. The effective edge is the area of the edge that comes into contact with the snow when you turn, gripping the snow and preventing you from skidding out sideways.

Base – Bases are pretty much all made of a polyethylene material known by the brand name P-Tex. They can be divided into two broad types: Extruded bases are made by squeezing P-Tex out of a machine like sheets of lasagne. These are cheap to produce, tough, and easy to repair, but generally don’t slide as quickly as sintered bases. Sintered bases are made by grinding bits of P-Tex into granules which are then melted together. They absorb wax better and ride quicker than extruded bases but need to be serviced more regularly.

SHAPE

The shape of a board defines how quickly and easily it turns, and how well it performs in different snow conditions. In most boards, there are two main factors that affect these characteristics – length and sidecut. Longer boards with directional sidecuts tend to be better in powder, while shorter twin nish or twin boards are usually better in the park or on rails. Some boards also have specially shaped tails that make a difference.

Length – The length of a board affects how well it performs indifferent conditions – longer boards have more surface area, and so float easier in powder. Shorter boards can leave you floundering. However because they are bigger they are often trickier to spin, making them more difficult to ride park or jib on. The most important thing to remember about board length though is that it’s all relative. A board that’s massive to a 4’ high midget will seem like a toy to a 7’ 8” freak – both would find boards at the extreme ends of the length scale impossible to control. So don’t just buy the longest board available and think it’ll turn you into the next Xavier de le Rue – check our length calculators on page 70 to see which size will suit you for different conditions.

Sidecut – The sidecut is the ‘bite’ taken out of the side of the board that dictates how sharply it turns. It is usually measured by the radius of one or more circles. Deeper sidecuts are generally found on boards that are built for hooning it around at high speed. By contrast a lot of dedicated jib boards tend to be wider with a shallower sidecut because this makes them more stable and more forgiving if you scuff a landing.

Special shapes – Some boards feature specially shaped tails to help them float in powder. Usually these are a variation on the classic swallow-tail design which we stole – I mean borrowed –off surf boards. They often have pointed upturned noses as well. Another common special shape is the wide board. These are just like normal boards, but for people with bigger feet. See, it’s not complicated at all really this snowboard design stuff!

PROFILE

Up until recently, you could put most snowboards down on the snow, look at them side on, and you’d probably find they all looked quite similar. The profile of most boards remained largely unchanged since the introduction of camber in the late eighties. That all changed when Lib released the Skate Banana, and K2 the Gyrator, in 2007. These reverse camber, or rocker, sticks caused a sensation and started a revolution. These days, board profiles differ massively, and the profile makes a massive difference to how a particular board rides. There are pretty much infinite variations, but here’s the low-down on the basic categories.

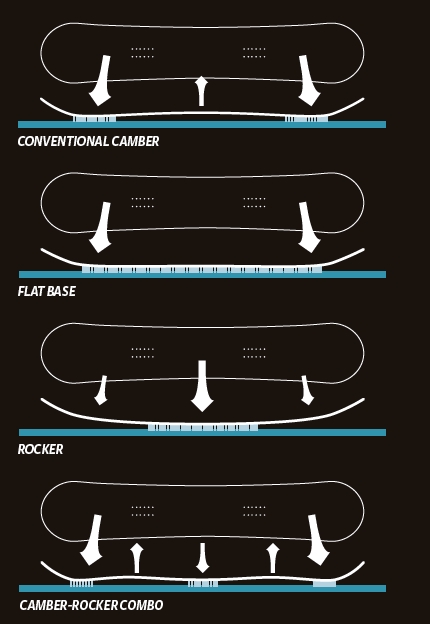

Conventional Camber

What does it look like? – When you look at a cambered board sideways on the base of a board touches the snow at four contact points near the tip and the tail, arching upwards between the bindings.

What does it do? – The board flexes with your weight when you carve on it and bends so that most of the effective edge touches the snow. When you pop an ollie, the concave profile helps provide extra springy resistance giving extra pop. Conventional camber is generally seen on boards built for charging hard, riding pipes or hitting big booters.

Flat Base

What does it look like? – These boards sit totally flat on the snow, apart from the normal turn ups near the nose and tail.

What does it do? – This keeps your entire effective edge in contact with the snow at all times, rather than putting all the pressure on four contact points. As your weight is spread evenly along the edge, it’s actually harder to catch an edge then on conventional camber boards. However flat boards lack the springiness out of turns and may have less pop. Several companies use completely flat bases on their pipe boards.

Rocker

What does it look like? – These boards curve upwards towards the tip and tail. The angle of the reverse camber and the point where it starts varies depending on the board and the brand. For example a lot of Nitro boards have rocker between the feet, while Capita’s boards tend to have it at the tip and tail.

What does it do? – The up-turned ends make it much more difficult to nose under in the deep stuff. Rocker boards tend to have a twitchier, livelier feel than their cambered counterparts, which means they may not hold an edge quite as well on hardpack, or feel as stable at speed. But the flipside of this is that it’s harder to catch an edge, so they’re more forgiving and much easier to jib and butter on.

CAMBER-ROCKER COMBO

What does it look like? – Combines elements of rocker and camber in an attempt to get the best of both worlds. Different manufacturers do it differently – some, like Signal, put camber between the feet and rocker at the ends. Others, like Lib Tech, do it the other way round.

What does it do? – These boards get some of the benefits of both rocker and camber sticks, though obviously aren’t as jibby or as solid as either extreme.