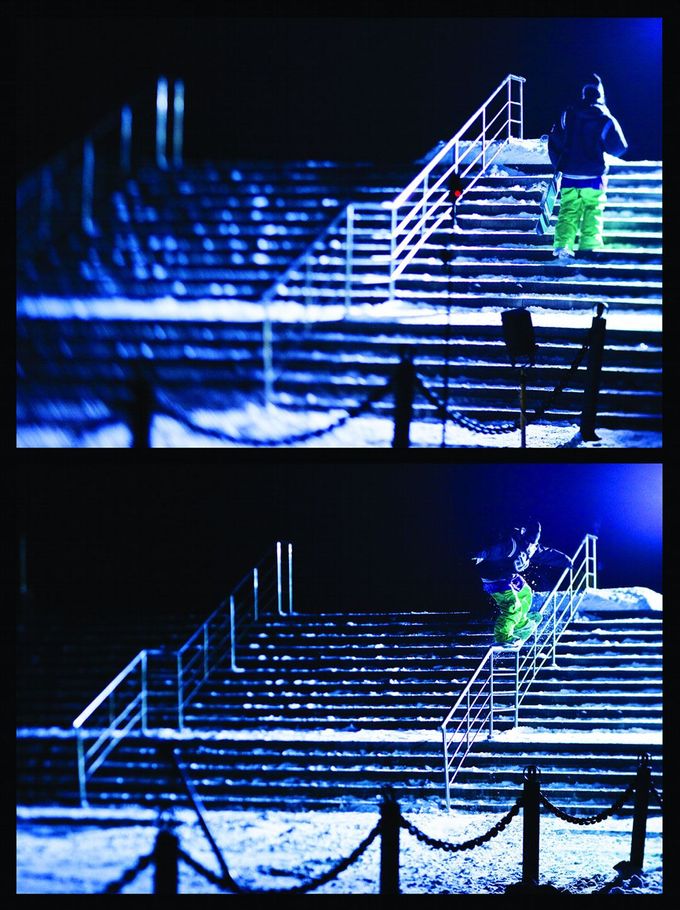

To understand why we push ourselves in the first place, it’s worth breaking the two factors – pain and humiliation – into more manageable chunks. The pain part of the equation is easy to de-construct. When faced with a gap jump, rail or steeper-then-we’re-used-to slope, there’s a voice in our heads that pops up and lets us know in no-uncertain terms that what we are about to do could result in egg-on-face – or a trip to A&E.

Naturally, the voice points out a few of the worst case scenarios. “What if you catch your edge on the run up,” it says, “and front flip straight over the take-off, landing eyeball-first on the sharp bit of metal that is undoubtedly a centimetre beneath the snow?” The voice will almost certainly take the form of a figure of authority such as a parent or teacher (mine is Mr. Logic from Viz), and run through a clip-board’s worth of equally dire and potentially fatal consequences.

“You’re going to overshoot the landing,” it says, “and land arse-first on a Victorian, iron fence.”

“’Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear – not absence of fear’, wrote Mark Twain”

The voice has good reason to dissuade you from engaging in horrendously dangerous activities. After all, the voice in your head is you – only it’s the absolute pussy version of you. The part of you that would much prefer to stay indoors, plug the Playstation in and spend the afternoon chasing mushrooms in a Super Mario go kart before having a pre-elevenses Müller Fruit Corner.

If you listened to this part of your person, you’d inevitably end up so socially withdrawn that within a year you’d be living on your own in a safe, English village like Dibley, having the Daily Mail delivered by a paper boy that you suspect of being a ‘hoodie’.

The trouble is, of course, that the voice is often right, and – when someone dares you to do a cartwheel on the wall of the Tignes Dam for example – it’s worth listening to its advice. So how do you know when to ignore it? I mean, if you look at things rationally, we shouldn’t be risking life and limb for anything.

And given the choice between a terribly painful death or, say, a gentle footscrub, what sane person wouldn’t be whipping off the socks and presenting our tootsies for their wriggly bubbly bathtime?