Taken from Whitelines Issue 102 Spring 2012

Words: Tristan

Imagine a school where sports lessons consisted of slopestyle practice, and the staffroom shredder was an Olympic halfpipe champion – rather than a white box made by Xerox. Incredibly, places like that exist. Tristan Kennedy went to investigate.

Snow is falling thick and fast outside the window. Inside, I’m sat around a cosy kitchen table talking to semi-sponsored rider Cameron Chaney about his plans for the season. He fires up his laptop excitedly to show me the latest edit he’s put up on YouTube and talks about the riders that inspire him – Andreas Wiig and Travis Rice. I’m sipping a beer as I nod along, asking questions and taking notes. Cameron is eating one of the home-baked cookies his mum’s just put on the table, and instead of a beer, is drinking a glass of milk. Which is just as well, because Cameron Chaney is only 11 years old.

Even by the youthful standards of today's professional scene, where kids are regularly sponsored and teenagers top X Games podiums, considering a pro career at 11 might seem a little bit ridiculous. But what makes Cameron different from every other kid who's ever dreamed of going pro is that his ambition is more than just a pipe dream. In fact, despite his young age there’s every chance he’ll make it, because Cameron is enrolled at the Vail Ski and Snowboard Academy (VSSA) – a school that specialises in turning talented young shredders into the pros of tomorrow.

“Not only do academy kids get coached by the same people who train the likes of Lindesy Vonn, it seems they follow similar regimes too”

Snowboarding quite rightly takes pride in its skate-influenced, dirtbag roots. But for years now the upper echelons of pro ranks (especially on the competitive side) have been ruled by riders who consider themselves ‘athletes’, and treat their snowboarding as a sport. You can argue til the cows come home about whether it’s down to increased competition, more money, or the Olympic factor, but the simple fact is that the era of top level snowboarders drinking like George Best before rocking up to ride the pipe the next day is over. These days, it’s all coaches, gym sessions and airbags for those at the top. In this brave new professional world, places like VSSA are playing an increasingly important role. In the same way that Arsenal or United’s youth programs nurture talents, snowboard schools (or snowboard academies as they should properly be called, to distinguish them form the kind run by red-suited ESF automatons) give riders an early advantage, setting them on the path to athletic success at a young age. Look at a list of today’s top pros and you’d be surprised at how many learned their tricks (and their trade) in these centres of excellence. Torstein Horgmo and Gjermund Braaten trained at NTG in Norway; Scotty Lago, Pat Moore and Mason Aguirre went to Waterville in New Hampshire; other academy kids include Louie Vito, Ellery Hollingsworth, Kim Rune Hansen, Alek Oestreng, Hannah Teter… the list is almost endless. The Mitrani brothers? Yep. Kevin Pearce? Uh huh, him too – the same school that Shayne Pospisil went to. Even riders who you wouldn’t instantly expect, like the free-spirited Helgason brothers, or the long-haired hippy Danny Davis, were trained in specialist institutions – the Malung school in Sweden and Stratton Mountain School respectively. With such an impressive list of high-achieving alumni, it’s obvious that these places are doing something right – snowboard academy graduates have won pretty much every accolade going in recent years. But how exactly do they work? And what impact does their increasingly professionalised approach have on snowboarding as a whole? That is what I’d come to Colorado to find out.

*****

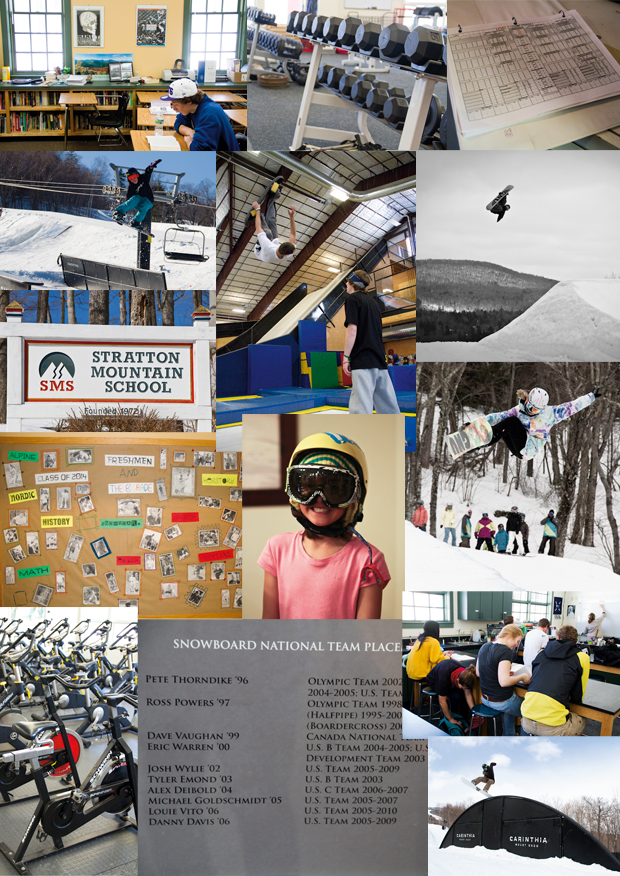

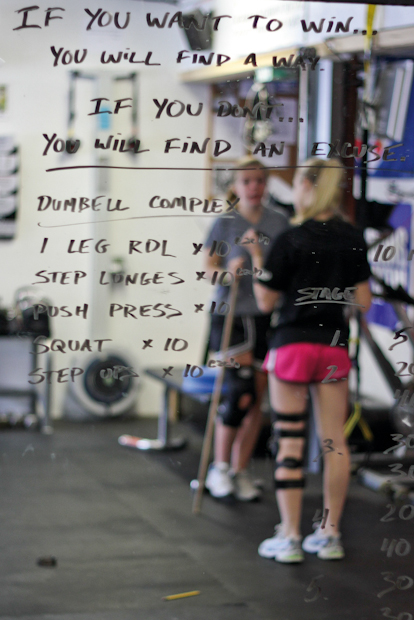

Some of my questions are answered the following morning. VSSA’s training program is based at the Ski & Snowboard Club Vail, a small squat building on the edge of the pistes. It’s half-term, so there aren’t any conventional lessons going on, but the majority of the kids are already out on the hill, having got up especially early to train in the pipe at neighbouring Aspen. Inside, a group of students nursing injuries are working out. Anna, who’s busted her ACL, is timing her friend Molly on a chunky stopwatch, counting her reps. The walls of the room are mirrored, and covered not only with instructions on how best to use the machines, but also with motivational slogans. Above a list of exercises (“step lunges x 10, squats x 10, push press x 10”) staff have written: “If you want to win, you will find a way… If you don’t, you will find an excuse”. A printed sign stuck up above a row of exercise bikes asks: “Are you working harder than your competition?” while underneath the medicine balls, there’s the declaration: “Champions are made here”.

This academy program is a collaboration between the Ski Club and a local Eagle County district school, so students take their academic lessons in a different building, but it’s still remarkable how different the quiet, concentrated training taking place in this room feels from most schools. On a normal day they’d be combining academic study with this kind of gym work, but it’s obvious from watching them that for most of these kids, this is where the real work gets put in. Katie, a blonde girl who’s adjusting an elaborate knee brace between exercises (she busted pretty much every ligament going on a summer trip to Chile) explains: “I used to train over at Winterpark Ski Club, but it was nothing like this, we didn’t do the gym work. It’s good, it helps you build strength and stuff, so you can come back quicker.” She can’t be more than about 15, but already, her attitude to training, injury and recovery is that of a full-fledged professional athlete. As I’m chatting to her, the club and school’s “Human Performance Director” strides in to check on his charges’ progress.

“Call me JC,” he says, offering an extremely firm handshake. John Cole is a Vail local from a professional skiing background. With his short hair, tight t-shirt, and brisk manner, he is every inch the fitness instructor. His office just off the gym is filled with brightly coloured bottles containing protein supplements, and he sips on a Gatorade-branded bottle as he talks me through the various courses the school runs. They cover everything from cross-country skiing to slopestyle, and produce athletes who compete at the highest level across the board. But then that’s hardly surprising because as JC says: “In terms of what we offer and the facilities we have, it’s incredible.” He gestures round the room “This gym for example. There’s a running joke that I have the most expensive room in Vail – there’s something like $85,000-worth of equipment in here.” It’s not just the facilities that are impressive either. JC himself is supremely well-qualified (one wall of his office is given over almost entirely to the various diplomas and awards he’s amassed over the years) and entirely dedicated to helping the kids be the absolute best they can, well, in between helping to train professional athletes like Lindsey Vonn – the local girl who won a skiing gold medal at the Vancouver Olympics.

Around 150 children aged between 11 and 18 are enrolled on the VSSA program at any one time. In the winter, they’ll be up the hill training from 8am til 12pm four days out of five, before heading to school for their conventional lessons. In the autumn and summer terms, they’ll do school work in the mornings, before spending their afternoons on this kind of conditioning work in the gym. Assignments are designed to be flexible, so that kids travelling for competitions can meet their deadlines, and everyone has a laptop so they can work on the road. JC explains: “All the pupils get the opportunity to train and compete, but out of the 150, there will be 40 or so‘elite’ athletes.” These kids (usually aged 15 or over) are the ones who have shown serious competitive potential. While younger years and more casual riders will do generic fitness training, these elite athletes have personalised fitness regimes. I’m shown one elite snowboarder’s folder – it’s full of graphs detailing exactly what he needs to be doing when, so he can reach peak fitness for his competitions that winter. It’s serious stuff – not only do academy kids get coached by the same people who train the likes of Lindsey Vonn, it seems they follow similar fitness regimes too.

“The era of top level snowboarders drinking like George Best before rocking up to ride the pipe the next day is over”

Of course, there’s more to being a pro snowboarder than just fitness, and turning youngsters like 11-year-old Cameron into the pros of tomorrow isn’t going to happen by making them into mini-Schwarzeneggers. But it’s the other stuff they offer around training that helps make snowboard schools like VSSA so special. There’s the South American summer trips, the advice and help with competitions and travel, and the fact that the school’s staff will petition comps like the X Games to give their best students wild cards. With an incredible wealth of combined experience, schools like this can give their pupils advantages that even the most dedicated of parents couldn’t hope to replicate. As JC points out, they even have access to a sports psychologist, helping them generate the kind of mental strength that those gym banners demand they display. “We’ve got a guy who from the University of Denver, which has one of the best programs around. The professors there are working with NFL stars and national teams you know?” On top of all this, a short distance down the road, VSSA has access to the secret weapon used by freestyle snowboarders from around the world – Woodward at Copper.

*****

The original Woodward started out as a gymnastics training facility in Pennsylvania, offering summer camps – an all action version of the summer camps that most American kids seem obliged to take in their summer holidays. They soon branched out into skate and BMX camps, and a few years ago hooked up with Copper Mountain in Colorado to create a unique indoor ski and snowboard training facility. Based in a specially-constructed barn next to Copper Mountain’s fire station, Woodward is like a teenage park rat’s wet dream, with skate ramps, a huge bowl, multiple trampolines, and snowflex kickers into foam pits. The walls of the lobby are decorated with old snowboards, and a guitar, while the stairs are festooned with inspirational quotes from the likes of Danny Davis and Terje Haakonsen.

I’m lucky enough to spend two days alongside Colorado-based Brits Nate and Seb Kern, being put through our paces by one of the coaches. Starting out with forward rolls on foam mats, we soon progress to misty flips into the pits and frontflips off the trampolines. A row of practise boards sits next to the tramps, giving us an opportunity to work on grabs and tweaks on a trampoline before taking it to the snowflex beasts next door. The gradual steps up, from mats to tramps, to having a board strapped to your feet, is perfect for trying new stuff, and despite not being the most gymnastic of riders, I’m soon happily hucking frontflips into the foam. With a video camera set up so we can watch our tricks, and the hugely experienced Chris Pappas (who’s been riding since 1977 and used to compete alongside Terje) as our coach, progression is pretty much inevitable. Without the threat of a painful stack, the speed that you learn new tricks is massively accelerated – one guy in our group nearly lands his first double backflip. Such is the confidence that foam pits and tramps give you, that in the space of a morning, I feel like I’ve tried more new tricks than I would in a week in the park. It’s no wonder copycat centres are springing up around the world, like the new multi-million euro Freestyle Academy in Laax. As I walk out, I can’t help agreeing with a Kelly Clark quote I spy on the stairs: “There’s no place like foam.”

“The fact that the gym is at least twice the size of the school library tells you where the focus of these institutions lies”

According to Phoebe, the centre’s director, snowboard schools from across the country run trips and training weeks here all the time. Most riders wouldn’t have access to these kind of facilities until they’ve turned pro, but just as they get serious with the gym work from an early age, it seems academies get their kids learning on trampolines and in foam pits right from the start. And then, of course, there’s the bread and butter of these snowboard programs, the stuff that really makes these kids into ESPN superstars: Taking what they learn in centres like Woodward to the mountain.

*****

Two weeks after my visit to VSSA, I get a taste of what this on-hill training looks like. Strolling up from the parking lot to the bottom of the pipe in Mount Snow, Vermont, I find the coaches from Stratton Mountain School. SMS is the alma mater of Louie Vito and Danny Davis, and one of the best-known snowboard schools around. Being based in the same resort as the US Open no doubt helps its reputation (the previous day I’d watched several SMS pupils, both past and present, do seriously well in the contest) but it’s the history that really secures it. SMS was one of the first schools to welcome snowboarders as well as skiers, launching a snowboard program in 1993. One of the first graduates of this program was a local Vermont lad named Ross Powers. After leaving school in 1997 Ross did well. Very well. He joined the Burton global team and won a bronze medal in Nagano in 1998, before taking gold in front of a home crowd at the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City. More recently, he’s returned to his roots, and was appointed director of SMS’s snowboard program in 2010. He’s now training the next generation of American Olympic heroes.

It’s definitely strange seeing a genuine superstar playing the role of teacher. But then it’s not everyday you see a class of school-kids lapping a perfectly shaped pipe. Certainly it’s different from school sports lessons I remember, which seemed to largely consist of being shouted at while trying (and failing) to fathom why I was supposed to care about a game as desperately pointless as rounders. The kids have started early, and are all encouraged to take a few pipe runs before some of them split off to concentrate on slopestyle. Ross and one of his fellow coaches stand at the bottom of the slope, filming them with handheld cameras – they’ll review the footage later – and giving them pointers before they get back on the lift. Another coach stands at the top of the pipe giving them hints on what to consider for each run, and watching them down. “There’s four of us full-time coaches, plus another part-time coach in the winter,” Ross tells me later, “and we’ve got 32 kids on the program this year.” With such a high coach-to-rider ratio, it’s no wonder that talented young shredders come from all over to study here. “We’ve had kids from New Zealand, we’ve got a girl from Australia, a girl from Canada…” Ross says. “I guess cos it’s a really good program, and it’s growing every year. When I was at SMS, we had five of us on the snowboard program, just one part-time coach, and we’d just do all our gym work and stuff with the skiers in the spring and fall.” These days, it’s all much more tailored to snowboarders’ specific needs. Kids in the Cross-Country skiing program and the downhill program study alongside snowboarders, but their on-hill training – and even their gym routines – are designed differently. With snowboarding, the emphasis is on producing complete riders. “We make sure the younger kids do a bit of everything. Slopestyle, pipe, boardercross. We don’t require that they do alpine racing, but some of them do and it helps with their edge control, their speed and everything. As they grow older it is more of a freestyle program, and they can specialize, but we still support boardercross in a big way too.” The results of this kind of training, especially when combined with the kind of gym routines I’d seen in Vail, are impressive. Mike, who can’t be more than about 15, is trying cab 10s in the pipe. Hunter, who one of the coaches describes as “the next superstar”, is lofting steezy back rodeos off the biggest kickers in the park. And even the youngest kids are getting decent air on their pipe runs.

“I dont think any of my teachers could drop into the pipe at the end of a lesson and go eight feet out with a beautiful, tweaked out method on the first hit”

As I watch them work, I’m intrigued by the relationship between the coaches and their charges. It’s respectful, as you’d expect given they’re at school, but they chat more like riding buddies than strict teachers and obedient pupils. The fact that both staff and students are on the hill because they’re doing something they love definitely changes the classroom dynamic. Hearing young Cameron talk about his coach Jeremiah back in Vail, there was a tone of hero worship in his voice that I don’t think I ever felt for my teachers. But then I don’t think any of my teachers could drop into the pipe at the end of a lesson and go eight feet out with a beautiful, tweaked out method on the first hit, like Ross does. He’s clearly enjoying himself as he rides to the bottom throwing classic straight airs, and it’s easy to forget he’s not ten years younger and topping podiums. But once he unstraps, he’s back in teacher mode, rounding up the kids and piling them on buses back to school.

Because there’s more to these kids’ daily routines than just shredding. SMS prides itself on its academic record, and its glossy prospectus boasts of children who’ve gone on to Ivy League colleges like Dartmouth and Brown. A tour round the school reveals surprisingly conventional lessons taking place. Kids are learning about blood groups in a science classroom, while another class is reading Huxley’s Brave New World. And while they’re given some flexibility when it comes to fitting in assignments around comps and travel, it’s not like anything goes – I wander into one room adorned with Hamlet posters to find a surly-looking snowboarder in detention, a scene I recognise all too well from my own school days. As Alex Lehmann, the Dean of Studies, explains: “We teach a proper curriculum, but we tailor it obviously. It’s all about flexibility, and if not everyone gets the assignments in on time, that’s usually OK, but SMS isn’t only about the sports – we want to give the kids the opportunity to do both well.”

That said, when we stop into the gym, it’s once again obvious where the focus of these institutions lies. The fact that it’s at least twice the size of the school library says a lot. As you walk in the door, two rolls of honour celebrate the achievements of former pupils: “National Team Placements” reads one, while the other proudly lists the significant number of “Stratton Mountain School Olympians”. This, rather than academic achievement, is what SMS and places like it are really all about.

“Are we getting to a point where rock n' roll pros won't exist any more, where hours of gym work and a serious approach will be needed to reaching the required standard?”

*****

Of course, all of this raises some questions – holding the Olympics up as the absolute pinnacle of achievement makes many snowboarders uneasy. When we interviewed him recently, the Quebecois jibber LNP (who admittedly isn’t known for his restraint with either his choice of words or his clothes) didn’t hold back on what he thought of academies. “I feel like that shit’s just killing snowboarding… I feel like it’s just gonna become a sport, which it was never meant to be. You don’t need a fuckin’ coach to snowboard, you don’t need to train for it. It’s like if you had a coach running round a skatepark, you’d be like ‘that’s just stupid’.” There are always gonna be rock n’ roll riders following in the footsteps of Shawn Farmer instead of Craig Kelly, but voices of dissent come from quarters you wouldn’t necessarily expect too. Mason Aguirre who graduated from Waterville into a successful pipe career, told Whitelines recently: “Going to snowboard school was incredible for the opportunities it gave me. But the thing is with academies is they push you down one route, they want you to do the competition thing. In the end that was the reason I quit the US team, ‘cos it all got so serious. They wanted to drugs test me and I was just 16. I didn’t even smoke weed then or anything, but I didn’t want that kind of stuff.” When you consider that most snowboard schools started out as institutions for elite skiers, perhaps the bias towards competitions is understandable. But is that necessarily a good thing for snowboarding? Are we slowly but surely getting to a point where rock n’ roll pros won’t exist any more, where hours of gym work and a serious approach will be needed to reach the required standard? And what hope for aspiring British kids in this brave new world? Are regular visits to the dryslope/snowdomes followed by a few hedonistic seasons in the Alps still a platform for a serious career? Or will snowboard schools kill off any chance of us producing another Jenny Jones?

And then of course, there’s the question of cost. Incredibly, for those who live in the catchment area, tuition at VSSA – as a public school – is free, although obviously travel and competition costs have to be paid for. Tuition at Stratton Mountain School at $42,900 for a year’s boarding, is not. Nor is it at most other snowboard academies. OK, so snowboarding has never exactly been a poor man’s past-time, and scholarship schemes (like the Ross Powers foundation which helped Danny Davis meet his SMS tuition costs) do exist, but the question remains – are these schools elitist? Is there a danger that pro snowboarders become identikit pipe jocks who’ve got to where they are because of expensive training and strict fitness regimes rather than natural talent and a love of the sport alone? Is snowboarding, as LNP put it, in danger of becoming “just another fuckin’ sport?”

These questions are swirling round my head as I stroll around Stratton’s new campus. Yes, the facilities are incredible, and yes the opportunities academies offer are amazing, but what does the continuing rise of snowboard schools mean for snowboarding as a whole? A visit to the dorm rooms answers a lot of these issues. The teachers aren’t sure it’ll be presentable enough to show to a journalist, and in their heads, it may not be. But Connor and Hunter’s room, with its stickered up cupboards, smell of sweaty snowboard boots and sounds of Bob Marley on the stereo, does a lot to dispel my fears. This could be any young seasonnaires’ apartment. These guys may be training every day, but they don’t talk or think about it in those terms. If anything, the chance to take it further and do it every day fuels their stoke even more. They love riding for riding’s sake, and look up to self-taught renegades like LNP and former pupils like Louie Vito alike. Like Cameron back in Colorado, they’re just relishing the chance to ride as much as possible, and maybe having the chance to live every kid’s dream of going pro.

In 2010, more than 30 million Americans tuned in to watch Shaun White win his gold medal – 12 million more than watched that evening’s episode of American Idol. With figures like that, the movement of snowboarding from niche past-time to mainstream sport – and the rise of academies to train its future stars – is inevitable. But that doesn’t change the fact that what motivates these kids is not money, or fame, but the same love of the shred that’s driven kids to strap on boards and slide down hills since snowboards were first invented. As Terry Kidwell, one of the original pioneers and arguably the first true snowboard pro, told us: “These schools are just part of the sport now you know, the way it’s blown up. And if the kids are into it, why not?” Why not indeed?