Intro

-

-

Photo: Jeff Patterson Rider: Pat McCarthy

-

Photo: Christian Brecheis Rider: David Benedek

-

Photo: Calle Eriksson Rider: Ingemar Backman

-

Photo: Geoff Andruik Rider: Kale Stephens

-

Photo: Jools Smith Rider: Matt Macwhirter

-

Photo: Frode Sandbech Rider: Terje Haakonsen

-

Photo: Scott Sullivan Rider: Tristan Picot

-

Photo: Perly Rider: Romain de Marchi

-

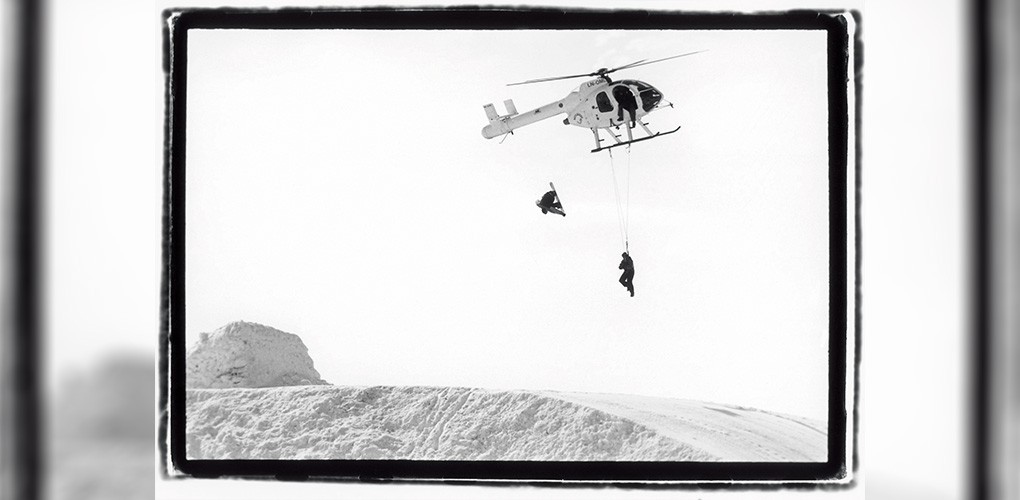

Photo: Jeff Curtes

-

Photo: Scott Sullivan Rider: Travis Rice

-

Photo: Jeff Curtes

-

Photo: Jeff Curtes

-

Photo: Nick Hamilton Rider: David Benedek

-

Photo: Markus Fischer

Intro

From Whitelines Issue 87 – December 2009

It is possible to fly without motors, but not without knowledge and skill

– Wilbur Wright, Aviation Pioneer

History is made up of people, deeds and places. An endless stream of names and dates which some folk (usually teachers in tweed jackets with elbow patches) get a hard on for, and others (such as the kid chewing gum in Ferris Bueller’s classroom) find boring as hell.

It’s all in the subject matter though isn’t it? Take sporting history. Way cooler. Roger Bannister collapsing after completing the first four minute mile (“Doctors and scientists said that breaking four-minutes was impossible,” he recalls, “that one would die in the attempt. Thus, when I got up from the track, I figured I was dead.”); Mohammed Ali vs George Foreman and the famous Rumble in the Jungle; or Usain Bolt crossing the Beijing finishing line at a canter having smashed the 100m record.

Moments like these live on because they show the rest of us mere mortals what’s possible. Surfers have appreciated this fact for ages, which is why they celebrate the old legends and make films like Riding Giants which are all about their pioneering exploits on do-or-die walls of water. Names like Waimea, Pipeline and Teahupoo echo through the surfing community, such is the power of these waves and the reputation of the men who first paddled out to tame them.

When it comes to marking our own historical sites, snowboarding is a little different. Certain kicker spots, like a great wave, remain fixed on the map as holy places – monuments to past feats and a rite of passage for the next generation of elite riders. Other important jumps were sculpted as one-offs – weather conditions, riders and manpower coming together for a short window before melting back into the landscape. Whatever the kind, snowboarding history is punctuated by a handful of special transitions which provided the stage for intense trick and/or amplitude progression. And the images these sessions left behind have captured the imagination of you and me. The following is a list of a few of these legendary kickers. As a topic to swat up on, it beats the Battle of Hastings doesn’t it?