Published in Whitelines Magazine Issue 93, December 2010

Words: Chris Moran

Whether he was a superstitious rider or not, Canadian snowboarder Ross Rebagliati can’t have been looking forward to Friday the 13th of February, 1998 – the day he was scheduled to appear in front of the International Olympic Committee and the assembled world media for a guaranteed embarrassing showdown, the likes of which even Dr Pepper couldn’t have made up. The story ended ridiculously enough. The Independent reported that “Rebagliati profited from a manoeuvre more involved than any he has ever attempted on a snowboard – the Legal Loophole.”

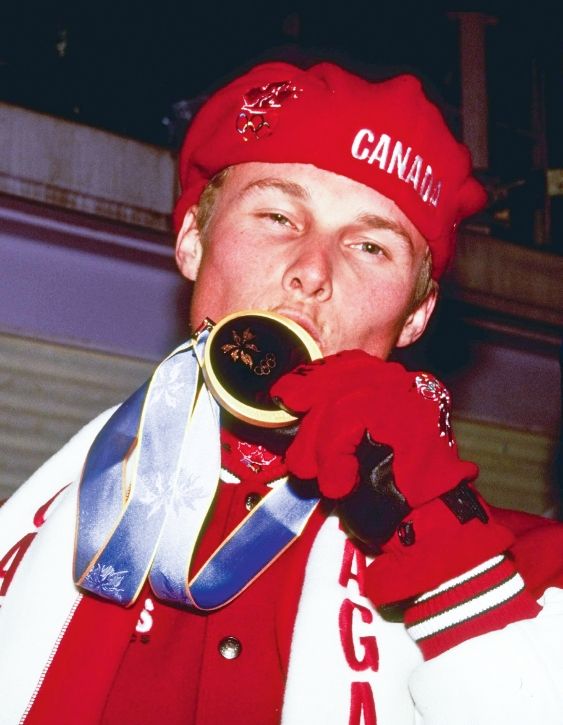

Born in 1971, Rebagliati discovered snowboarding in the1980s, and moved to Whistler BC in 1990 – just as the sport was exploding in popularity – where he trained as a racer. When snowboarding was included in the 1998 Nagano Olympics in Japan, many thought the new sport might not fit in as easily as the IOC hoped. In truth it was a marriage of convenience – ski ballet, curling and moguls were sports on the wane, and the IOC had turned to the rapidly growing sport of snowboarding to boost its portfolio. Snowboarding’s gain was one of mass exposure and increased pay-cheques for the top athletes, but many riders were dubious about jumping into the Olympics. Terje Haakonsen, the undisputed halfpipe king at the time, let his feelings be known when he shunned the games and went surfing in Brazil instead, telling the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten that “Snowboarding is about fresh tracks and carving powder. It’s not about nationalism and politics and money.” It was amidst this uncomfortable atmosphere that Rebagliati won the first ever snowboarding gold medal, taking the slalom win by two hundredths of a second over Italy’s Thomas Prugger. It was an impressive achievement, but one that was spectacularly overshadowed by the fact that he failed the subsequent winner’s drugs test after traces of marijuana were found in his urine.

The skiing community were smug, the IOC were embarrassed and the snowboarders laughed. The press, naturally, jumped on the story. For those reporting on a relatively incident free games, it was a dream come true.

“The 26-year-old claims he is a victim of passive smoking,” said the BBC, “and has told Canadian officials that he had been with a group of drug smoking friends in his home town of Whistler, British Columbia on January 31, the day before leaving for the Olympics.”

The IOC had literally no idea what to do. Marijuana wasn’t on their list of banned substances – presumably because they thought no athlete in their right mind would smoke weed and compete at elite levels of sport – meaning there was no precedent to follow. “Marijuana is not a performance-enhancing drug and in fact does the contrary,” said a befuddled spokesperson Carol Anne Letheren.

For Ross it was a scary time. His room was searched and he was interrogated by the Japanese police. Had he been caught with marijuana in the resort, he could have been imprisoned for up to five years. Looking back, Ross says he found it all strange.“Honestly, I didn’t go to the Olympics with a bag of weed,” he says. “I hadn’t been smoking for months and months to pass the stupid drug tests. I wasn’t into doping.”

The police, he says, made him feel “frightened like a prisoner of war” and claims being “called a cheat” by International Olympic Committee President Juan Antonio Samaranch, was humiliating. But the Friday 13th meeting proceeded and, since he hadn’t broken any of the IOC’s rules, his medal was begrudgingly re-instated. The New York Times reported the incident under the headline “Snowboard Dude Says: No Big Deal.” Author George Vecsey was angry at Ross’s treatment, claiming the IOC had “hung the kid out to dry with their gibberish,” and heaped praise on the Canadian, saying he handled the furore with poise. “I won my medal two times,” said Rebagliati. “They made a decision. They lost. That’s the end of the story.’”

Sadly it wasn’t that simple. Letters to newspapers and endless debates on TV made Ross a household name, for all the wrong reasons. He received hate mail, was snubbed by many, and even received death threats. According to one report he slumped into post-traumatic stress. His sponsors dropped him, the snowboard scene didn’t support him, and the Canadian sporting community wanted nothing to do with him.

“Things came crumbling down around me. I changed; I was a lot more happy-go lucky and trusting before those Games but afterwards I was traumatised, in the wrong state to handle the pressure.”

Ross went back to Whistler, became a real-estate agent and spent years “trying to restore my name and rectify my image and reputation.” Then he met Alexandra, a PR agent. “My wife was really the beginning of the rest of my life,” he says now. “She was able to rebrand my brand. Alexandra just wanted me to continue doing my snowboarding thing and live up to the celebrity and use the gold medal for positive reasons, for kids.”

Alexandra’s skills were tested a year later, when a character appeared in a Canadian soap opera bearing remarkable similarities to Rebagliati. ‘Beck MacKaye’ was a blond snowboarder from Whistler who’d won an Olympic gold medal. He was also – according to the publicity literature –“a blackmailing drunk who leaves a woman paralyzed in a hit-run accident.”

“I’m the only blond-haired, blue-eyed Canadian snowboard Olympic gold medal winner who lives in Whistler,” said Rebagliati at the press conference announcing his intention to sue the show’s makers CTV.“The character was a real loser… I didn’t like it that people would think that’s me.” Ross won the court case (though he won’t divulge the figure he settled on) and the show’s producers showed what they thought of the decision when they killed the character off in a bone-crushing avalanche.

While the court case was being prepared, Ross took time to author Off the Chain – a history of snowboarding aimed at kids. “If I had written this book any earlier, it would have been much darker,” he says. A year later he was back in the headlines when the Olympics rolled around to Vancouver and Whistler in 2010. Juan Antonio Samaranch got his long-awaited revenge, snubbing Ross by not even inviting the gold medallist to the games. “They think I’m an embarrassment,” claimed Ross, dejectedly.

But not everyone agreed with that assessment. In the search for a younger, hip candidate to spread their message of tolerance, The Canadian Liberal Party -the equivalent of the Labour Party – asked Rebagliati to run in Canada’s general election for the constituency containing Whistler.

Today Ross divides his time between managing his real-estate company, being a father to his ten-month-old son Ryan, and running the campaign for the Canadian parliament. “I really feel honoured to have been invited because a lot of times I wondered, ‘I’m famous, but is it for the right reasons? Do people really support me or do they think I’m a joke?’”

That particular question will be answered at the next Canadian General Election, and in the meantime the issue of cannabis legalisation looks likely to come up time and again during the debates in which Ross takes part. Clearly still an advocate of smoking (his Rebagliati Alpine Snowboard Training Academy makes the acronym RASTA, and his political page lists “jazz and reggae” as his favourite music), he has developed a way of seeing the funny side of his past infamy. “My message is for everyone to go green,” he said in a recent Sports Illustrated interview. “And I know what you’re thinking, but not that kind of green.”