Taken from Whitelines 104, November 2012

Words by Jon Weaver

Photos by Cyril Mueller

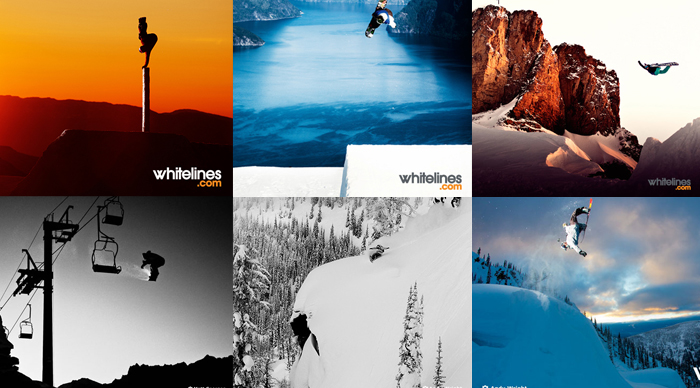

Iceland was once known only for fish, Bjork and the kind of martian landscapes popular in car commercials. Now, thanks to the Helgason brothers, the ‘Land of Fire and Ice’ is emerging as a legit snowboarding destination. Jamie Nicholls and the Nike team went to check it out.

***UPDATE: To watch an edit with all of the action from this trip, head here***

It’s funny, coming from England we always tend to have misconceptions about other parts of the world. Maybe it’s becuase few of us islanders actually travel that far; we’re too busy drinking beer and fighting when the pubs close early. But those of us who do spread our wings are quick to see the error of our ways. At school, all I was really taught about our cousins in the North Atlantic was that “Iceland is green, and Greenland is icy”. Not exactly a definitive guide. Thanks to the handiwork of Scottish shaper Graham McVoy, however, a lucky few of us were introduced to the natural beauty of Iceland a few years back, when he and Bjarni Thor Vladirson established the IPP (Iceland Park Project) on the Snaefell Glacier (what a name that is by the way!). Whilst there, we saw some tiny local kids with even tinier stances hitting the jumps, sending themselves as high as humanly possible. A few years later one of these kids would win the X Games with a web address drawn on for a mustache, putting his homeland on the map once again. His name was Halldor Helgason.

That was as far as the country’s fame went until the economic downturn lurched it onto the front pages around the world, when lots of people in the UK discovered they’d poured their savings into an Icelandic banking scheme that was “too good to resist” – and of course it failed. So, with a currency which had seen a rapid devaluation, what better time for a bunch of snowboarding chancers to visit?

This would be Jamie Nicholls’ first real street mission. How would he fair outside the park, where you have to scrape together snow, pull each other in, and ride stuff you’ve never seen before?

We had been in China for the Air and Style, checking the weather for Oslo, Stockhölm, Helsinki, Newfoundland, Montreal, Innsbruck, Munich – anywhere we could get some street stuff done in December – but the weather maps weren’t looking too helpful. All except one tiny corner of the world, nestled between Scandanavia and New York… So, after making some calls to Halldor, we booked next day tickets and headed for the capital, Reykjavik. Upon landing, it soon dawned on me that the capital doesn’t normally receive such epic snowfalls, for while the chaos wasn’t on an English level, the people were clearly exited to see so much snow in the city. At the Hertz desk I told the guy about our plan and he actually seemed stoked at the prospect of handing a shiny new van over to five dirtbag snowboarders, which would be unheard of in other places. I liked it here already.

Since I’d arrived a few hours before the riders and cameraman, I took it upon myself as a good team manager to go hunting for spots nearby. Now, having spent weeks driving around Austria in my time and only ever finding a handful of good rails, I knew what to expect. Maybe a diamond in the rough, but don’t get your hopes up. So off I headed to Keflavik, the nearest town, only to stumble straight into a zone which yielded at least three or four promising spots. Things were looking good! After picking up the riders and working out a schedule for the next few days, we headed out the next morning to have at it.

With such a talented crew I was excited at what we might achieve. First up was Jamie Nicholls, fresh from winning the Burton Rail Days event in Japan. This would be his first real street mission. Singled out for big things from a young age and keen to hit anything, a lot has been made of Jamie and his kicker riding ability, but over the last couple of years his rail riding has really stepped up – to the point where he can now go head to head with the world’s best, as he showed in Japan. However, while the Tokyo event included some big rails, it was still an artificial set-up with a perfect in-run and landing. How would Jamie fair in the streets, where you have to scrape together snow, pull each other in, and ride stuff you’ve never seen before?

The rail was located in a building site that was a kind of urban Marie Celeste, like people just downed tools and left. Eerie.

Then we had Ethan Morgan, who although only 20 has been going on jibbing missions for five years – his first, at the age of 15, was to Russia of all places. Since then he has filmed with the Isenseven crew a couple of times, bagging one end section, and as we arrived in Reykjavik he was underway with Standard Films. This was as good place as any to get his first shots for the new movie. The final spot on the trip was originally supposed to be filled by Kevin Bäckström, but a recurring broken arm kept him out so we drafted in Niki Korpela, a friend of the crew and a Finnish legend. Just days before he’d been serving in the army!

Our days up in Iceland soon fell into a familiar pattern. Wake up mid to late morning, get ready, grab some breakfast, drive around, scope, find two or three good spots (and at least 25 where Jamie would say “imagine if…”) then usually start building with the afternoon light fading and go long into the night, before getting home anywhere between 3 and 6am. Then repeat. Intersperse all that with various Subways, greasy hot dogs from the petrol station and other such unhealthy stuff, and that was pretty much the run of show up there.

We started things off at a curved double kink rail near the airport, but sod’s law our brand new generator decided against working. Not to be put off, Jamie started sessioning it in the darkness, laying down some tricks which most riders would be happy with in the daylight.

Next morning we were up early and back to the hardware store, which was where we first discovered how amazing the Icelandic people are. We’d actually bought the generator and duly got our money back no questions asked, before being sent to the side of the store where they do rentals. A nice guy in there said you needed a local address and driving license before they’d allow you to hire anything, so we explained the situation and the next thing you know we are walking out with an even bigger generator – the shop guy had actually put down his own ID as guarantee. That just doesn’t happen in many places.

The 12 kink was one of the toughest rails you will ever see ridden

So we set about getting the next set-up underway, a nose stall to drop, and after a successful few hours we were again amazed by the Icelandic hospitality. The spot was right beside a row of three terraced houses, from where we realised we were being watched by a lady and her children. Not normally a good sign. We finished the session around 11pm, and were quick to break down the snow and clear up the area. At that point the lady approached us; we were sure we were in for an earful because we had been a little loud, or her kids couldn’t sleep. Instead she ushered us towards her house, and still we were dubious. Maybe we’d made a mess up there or something? But no, she showed us into her lounge, where she had made up a full spread of tea, coffee, soft drinks, cakes, biscuits and snacks! It was raining outside in the darkness, and after being on the go all day it was like walking into heaven. She couldn’t speak English, and we couldn’t speak Icelandic, but she could see we were tired and wet and she was bringing tea and warmth. It was definitely one of the nicest gestures I’ve witnessed in my time snowboarding. Jamie could probably have moved in there if we had stayed a little longer. A good street set-up, with a Pizza Hut nearby and tea and cake on demand? Seems we weren’t a million miles from Bradford after all.

The next day we headed to the infamous 12 kink, which we had found by simply driving around Reykajvik. Approaching from a couple of kilometres back we could see a small rail in the distance; as we got closer, it kept getting bigger and bigger, until finally we were there and the size of this thing dawned on us. 12 long wooden kinks, more stairs than you could shake a stick at, and an in-run. Only trouble was it was colder than it had been in ages – or was that just a shiver down my spine?

Despite all the news we hear in the UK about “the downturn”, this was one of the first examples I’d seen of what it can do to a place. The rail was located on a regular housing estate which was mid-way through construction, but there was no sign of life – just broken windows, disused buildings and vacant land. It was a kind of urban Marie Celeste, like people just downed tools and left. Eerie.

The local economy’s loss was our gain, as it meant we had this monster of a rail to ourselves, with nothing but our own frozen breath for company. It took Jamie a lot of tries but thankfully he stomped it before our fingers on the record buttons froze off. It was one of the toughest rails you will see ridden, as the wood wasn’t straight, the speed you’d gained halfway down was faster than you would fancy riding down a slope, and the sides had a fair smattering of rocks and ice.

I look in my rear view mirror and see Niki head off over the gap… and keep going upwards…

The next spot was one we’d driven past a few times already, and whilst it looked good we were a little wary because it was right next to the highway and a huge Intersport superstore. But, this being Iceland, we figured the conspicuous location might not matter. From the road it looked like a fairly easy kinked rail, but on getting there it was pretty apparent the rail actually took in a 90-degree turn, and the kink itself was horrible. We were bummed and thinking it might not happen – that was until Ethan and Niki sized it up and had the vision of gapping straight onto the bottom section. Now this was something different, and would require more of a build than originally estimated. So we set about moving snow onto the landing, take off and in-run – quite the set-up. We ended up building for close to three hours, scraping every last bit of snow from the whole car park. Then, as always, came the ironic twist. It started dumping – puking in fact. If we’d just waited a little while we would have had more than enough snow.

Nevertheless, it was a good warm-up and we started to get after it. Niki Korpela, freshly let off the army leash, was willing to be the first rider, so we set about getting the van into place. The speed from a bungee wouldn’t be enough to clear the gap; we were trusting in Ford Transit power.

As you get older and take on more of an organisational role on trips, something funny happens when you see a feature coming together. Previously, all you could see is what amazing tricks would be possible. Once you get to a certain point, however – probably around the same time you realize that you’re never going to be a pro snowboarder – that enthusiasm turns to fear. “What if he catches his edge on the take off and slams into the rail?” or “What if he misses the landing and snaps his knee?” and “What if I drive too slow and he doesn’t make the gap?” It’s a strange feeling, but one which on heavy set-ups you just have to stuff to the back of your mind. This was one such feature.

Towing Niki in, then, I was paranoid about all the things that could go wrong if I didn’t drive at the same speed each time. In some kind of slow motion //Back to the Future// scenario, I was aiming to get up to 25km/h and of course went straight past that. Slingshotting Niki straight towards the kicker, I look in my rear view mirror and just see him head off over the gap… and keep going upwards! I jump out of the van run to the take-off, from where I can see his landing mark a good 10 foot past the rail. He’d pretty much fallen from 25 foot up in the air to flat. Niki seemed happy enough, though, and ran back up to give it another shot with a polite request for me to go a bit easier on the gas.

Second go he got the speed, but (maybe because of my sketchy driving) he drifted slightly off course. Third time lucky then? Keen as ever, Niki shouted, “Yep, lets’ go!” so I put the foot down and headed onwards. Checking in the mirror again, the speed and height looked good as I watched him disappear over the top rail, but I came over to see the other riders running towards him. I feared the worst. “Oh here we go,” I thought, “an injury.” Fortunately he seemed OK, it was just that the impact from the gap to rail had managed to snap his board clean in half.

Ethan then took up the mantel and set about it. Starting off with a gap to boardslide, he was dealing with the compression pretty well, and before long he was nailing seatbelt grabs into a boardslide. It was impressive to watch. The whole landscape of urban snowboarding has changed so much in the last few years. Back in the day you searched for a down rail and that was about it. Now – with winches, bungees and re-entries – snowboarding in the city is a whole new ball game. Movies like Patchwork Patterns, and riders like LNP and Scott Stevens, paved the way, and these days you don’t even need that perfect down rail anymore, just an eye for a spot and a little creativity. I used to love hitting urban rails myself, but there are things kids look for nowadays which I don’t even see.

On the way home from the gap, the GPS was playing up and we got a bit lost. But it proved to be a blessing in disguise when we found ourselves directed down a residential street on a nice slope – always the magic potion for street rails.

Sure enough, we quickly spied a dream downrail coming up on the right: in-run from a side street, a perfect rail and a landing. I had flown home by the time the guys returned to hit it up, but judging by the texts from filmer David Doom, the session went well. “Jamie killing it,” buzzed the phone, followed by “OMG Jamie 16 tricks on the down rail. 16 TRICKS, machine!” That was a nice way to be woken up.

Iceland is one of those rare places where you can find rideable terrain around every corner

The key to a good rail trip – when you’re going to be up all night, eating badly, not sleeping enough and riding hard – is that the crew has to work as one. If someone sees a potential spot then they might be the only one who fancies it, but the whole crew has to jump in and work together to make it happen. That was how it worked on Jamie’s downrail: everyone built it, and he sessioned it and got the shot. The second thing is just to understand how each personality contributes to the team. You need someone to keep spirits up, someone to take charge of where you’re headed, and riders who are prepared to shovel, scrape and sweat. That’s where trips like this are different to riding a park in a resort. All you will see in a magazine or video is the final shot, and no doubt a few kids reading this are thinking, “Yep, I could do that trick there”, but there’s an unseen story behind every image.

Iceland is, though, one of those rare places where you can find rideable terrain around every corner – from the easiest 10-stair down rails to huge ledges that could do you some serious damage. It’s no wonder that the Helgason brothers and their compatriot Gulli Gudmundsson have had such stand-out parts recently. They have snow on the ground early, there is little chance of getting busted, the people are friendly and they have more spots on lock than any other part of the world. Ours was also the first trip to be blessed with snow in the capital Reykjavik, an added bonus that meant 90% of the stuff we shot hadn’t been ridden before.

On top of all that, Iceland is simply one of the most beautiful places on earth, where stunning coastlines meet the freezing Altlantic and natural hot springs erupt in the strangest of locations. It was one of the most memorable journeys I’d made in many years of snowboard travel. As an MC and team manager, most of the time I find myself visiting events. The course is pre-prepped; you sign in, collect your bib and a start list. It’s all so mechanical. On a trip like this one, you have to work everything out for yourself; you build every feature with your own blood and sweat. But, as they say, you get back whatever you put in.